Chapter 6: the weight of a word no one wanted to say

The hospital didn’t run on clocks that week. It ran on countdowns. On waiting. On fasting.

On this brutal loop: Wake up. Hold still. Don’t feed her. Hold her again.

The Monday after we were admitted, I was already learning the rhythm of this place. I knew the early shift nurses and the late shift nurses. I knew how to spot a resident trying to look confident and a fellow pretending to make decisions they didn’t have authority to make. I knew where the coffee was. I knew how to walk the halls.

Because that’s what we did.

We walked.

At 4:30 a.m., Evelyn would wake up from a restless half-sleep in my arms—confused, hungry, whimpering. I wasn’t allowed to nurse her. We were fasting for the MRI. No solids. No milk. Nothing by mouth. Just one quiet baby girl trying to understand why her mom wouldn’t offer her the one comfort that always worked.

So I walked.

Hallway after hallway, past the mural of the sea creatures near imaging, past the elevators, past the fish tank that hadn’t worked in years. We passed other parents in the same pattern. Tired. Hollowed out. Pushing time forward by pacing in circles.

At 7 a.m., the cavalry arrived.

My mom. My dad. Zed. They didn’t take shifts; they created them. Dad would bring coffee and a muffin. Mom would hold Evelyn and let me go to the bathroom. Zed would take my keys and check the house, bring back a change of clothes I hadn’t even asked for. They were a human infrastructure—no one assigned, no one scheduled, but somehow it all just worked.

You never, ever forget the people who were there in your most vulnerable moments.

And all the while, Evelyn stayed in the center of the wheel.

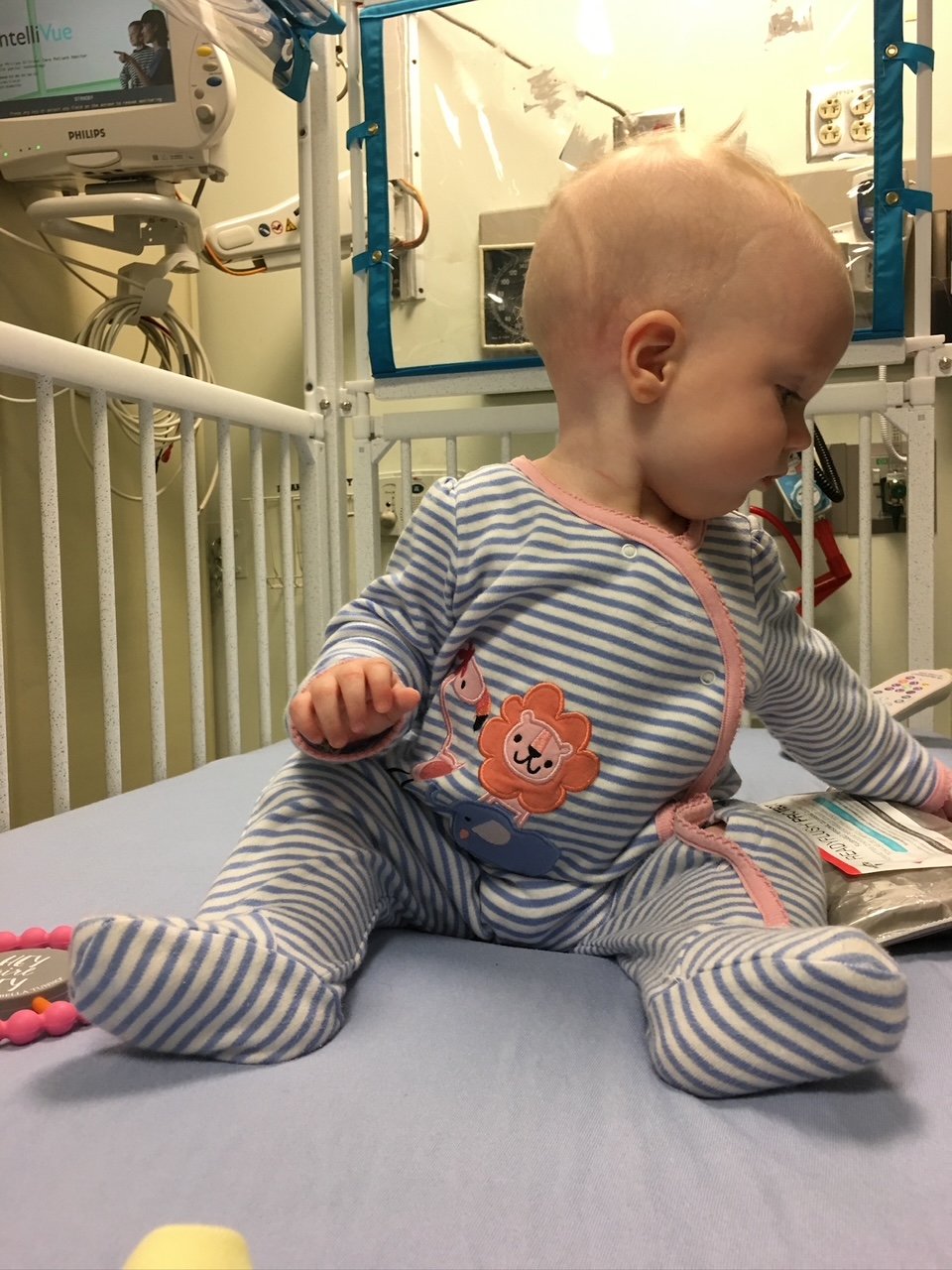

Cranky. Sleepy. Her eyelids heavy like someone had tied tiny weights to her lashes. One eye still drifting off to the side. Strabismus, they called it. Exophoria. A lazy eye caused by something—something we were about to start naming.

By 9 a.m. on November 5, 2018, we were no longer in the realm of “just in case.” This was no longer a precautionary peek. This MRI—thin-cut, with gadolinium contrast, and a sedation protocol that required full general anesthetic—wasn’t just a scan. It was a line in the sand.

And Evelyn—my baby, my beautiful, bright, stubborn seven-month-old daughter—was going under. For real. Fully under.

This was no “rapid FIESTA.” No 10-minute emergency tunnel sprint. This was the kind where they use words like mesencephalic targeting, periaqueductal hyperintensity, and diffuse mass effect. Where they prep a lumbar puncture “just in case.” Where the term “suspicious lesion” begins to stretch its claws.

They told me I couldn’t go in with her this time. “Not when it’s general,” they said, almost apologetically. But I walked her there anyway. From the dimmed MRI change room down the sterile hallway, through double doors that hissed shut behind us. She was fasting—hadn’t eaten in hours. Her body, tiny and tense, was already fighting the sleep it didn’t choose. And they were going to force her to sleep anyway.

When we reached the table, the anesthesiologist placed the gas mask over her mouth while I held her. The moment the gas touched her skin, she screamed. She kicked. She writhed. It took four adults to hold her still enough to let the drugs work. I held her hand as long as they let me, until her muscles slackened and her eyes rolled back.

Then they told me to go.

I walked out backward. They didn’t have to kick me out—I left on my own—but the door still felt like a betrayal when it clicked shut. I remember pressing my back to the hallway wall and sliding down until I hit the floor, trying to breathe as though my lungs hadn’t just shattered.

It would take an hour and a half. But time bent around itself in that waiting room, in that purgatory of beige walls and magazines I couldn’t read. I couldn’t sit. Couldn’t think. Couldn’t talk.

When she came out, I was already standing there, insisting: Call me the moment she stirs. Because Evelyn didn’t wake quietly. She didn’t drift into consciousness like a child in a cartoon. She erupted. Like a siren. Like a whale breaking the surface of an ocean, wailing so deep it sounded prehistoric. Nurses learned fast to call me early.

“She’ll fight you,” I told them. “She doesn’t know where she is, but she knows it’s bad.”

She was always fierce. Still is. But that day, she thrashed in my arms, furious and groggy and so, so small.

Later, when the report came in, I read words I wasn’t supposed to read.

“Asymmetric thickening and enlargement of the right-sided superior colliculus…”

“Faint ill-defined hyperintense signal in the periaqueductal region…”

“Extension into the caudal aspect of the thalamus…”

“Elevated choline. Myoinositol peak…”

I wasn’t supposed to read it, because Dr. McAuley told me not to. “Don’t read the reports,” he said. “Don’t Google. You’ll find things you don’t need to see.”

But of course I read them. Of course I Googled. And what I found was terrifying.

Choline and myoinositol peaks. Terms that, once searched, tie themselves to brain tumors. To high-grade gliomas. To the words I wasn’t ready for. Diffuse. Inoperable. Malignant.

On that day, I walked into CHEO thinking we were escalating care. I didn’t know we were walking into the territory of cancer.

That scan—the one that would later be referenced again and again in every future MRI—showed progression. More mass effect. More ill-defined brightness near the cerebral peduncle and into the thalamus. More evidence that something was growing. And not going away.

They hadn’t said “cancer” out loud. Not yet. But the reports did. They whispered it. Between the technical language. In the white space between words. In the implication of choline/NAA reversal and mass effect and lack of enhancement that felt less like a reprieve and more like a dare.

I didn’t sleep that night.

The findings started to line up that night, like a line of ghosts.

“Stable asymmetric thickening of the superior colliculus,” they said.

“New faint hyperintense signal in the periaqueductal region,” they added.

“Mass effect on the aqueduct appears subtly increased.”

I didn’t know those terms yet. But I could feel the shift in tone.

By November 6, more sequences were ordered. T2-weighted, FLAIR, gadolinium contrast, and the spectroscopy—that one stuck with me. They were looking for brain chemistry now. The MRS showed elevated Choline and a peak of Myoinositol—markers that whispered about fast-dividing cells. Tumor cells. Glioma? Maybe. Maybe not. They weren’t sure.

But Dr. McAuley was watching the scans with his arms crossed and his mouth closed. He sat down with me that night and said:

“Don’t Google anything.

Don’t read the reports.

Pediatric tumours are very different than adult ones.

We are going to walk through this one step at a time.”

And that’s how you know something is real. When the straightest shooter in the room tells you not to look.

And Evelyn? She slept on me, like always. As if nothing had happened. As if she hadn’t been drugged, scanned, poked, and left screaming in a glass room before being placed back in my shaking arms.

I held her until my arms went numb.

And I told myself, Don’t Google again.

I lied. I always Googled again.

And I always remembered that morning—the one where the scan became real. Where everything changed. Where the door closed behind me and I had to decide what kind of mother I was going to be.

Because now, we were in the fight. And the enemy had finally said its name. Even if only in the subtext.

And it was going to take everything to hold on.

The next day, November 7, they moved to the spinal cord.

A lumbar puncture—another test. Another line crossed.

They said it was to look for infection. Inflammation. The improbable. “To rule things out,” they said. But I’d already learned what that phrase really meant: To edge closer to what they’re afraid to name.

Evelyn curled into me in pre-op, her fingers digging into my collarbone. She knew. Somehow, she always knew. I could feel the fear leak out of her like steam, not loud, not dramatic—just a silent clinging that said, Please don’t let them take me again.

She went under again. She always went under.

And when she came back, she looked like she’d been crying in her sleep. Her lashes were wet. Her fists were clenched. But she didn’t have the energy to scream. She just whimpered, and then went still.

The results came the next day:

Bands: Elevated.

Mononuclear cells: High.

34 white cells in the spinal fluid.

It wasn’t a diagnosis. But it was an alarm.

Not “normal.” Not “clear.”

Something was off. Something was happening. Something brewing in the cerebrospinal fluid, whispering that the immune system was responding to something it couldn't quite kill.

We stayed. Another day. Another scan. Another round of blood work.

We stayed in this awful holding pattern.

Just me and Evelyn.

My parents, showing up in shifts like loyal sentinels.

Zed, running the perimeter of my old life—keeping it intact.

And every hour, another test.

Another specialist.

Neurology. Ophthalmology. Infectious Disease.

Neurosurgery, again. Always them.

And then came the meetings. The daily rounds that felt more like war rooms.

I remember one morning in particular—maybe Wednesday, maybe Thursday, time was water—when I was holding Evelyn in the ward and the entire medical team walked in. Seven, maybe eight white coats. All of them serious. All of them quiet.

The look on their faces told me everything before they spoke.

Not good.

I was still hoping. Still begging my brain to consider the less dramatic endings. Maybe post-infectious inflammation? Maybe something viral? Something strange but survivable?

But the scans were getting worse. And the words were getting softer.

They called it “an evolving lesion in the midbrain.”

They said “we need to observe closely.”

They never said tumor. Never said Cancer.

Not then. Not yet.

And then Dr. McAuley said it all in six words:

“This is real. You’re not wrong.”

That broke something open. Not my hope—but the illusion that I was being hysterical. That maybe I’d overreacted. That maybe this wasn’t as bad as it felt. I hadn’t overreacted. I hadn’t misunderstood the signs. I’d walked my baby into the emergency room because something was truly, deeply wrong.

And now they were finally saying it without saying it.

That night I slept—or didn’t sleep—in the hospital recliner. Evelyn on my chest. I was still in my jeans. Still in yesterday’s shirt. I didn’t care. My body hurt. My neck was stiff. My tailbone screamed. But I wasn’t putting her in that crib. Not with a brain I didn’t trust. Not in a ward where I wasn’t sure who’d notice if she stopped breathing.

She needed to be on me. My breath rising against hers. My heartbeat a metronome against her ear.

I didn’t trust the night nurses. I didn’t trust the chart. I didn’t trust whatever story the doctors were half-telling.

But I trusted my people.

Thursday night was wine and pizza and artificial comfort. Zed brought levity, my mom brought presence, and I brought the heavy thing in the center of it all. Evelyn had finally fallen asleep. We tried to laugh at memes. We tried to believe the 90%.

I cried into my wine glass, my mother rubbing my shoulder like it could fix something. Zed cracked a joke about wine pairings for existential dread.

And then my phone lit up with a FaceTime call. John and Emma, still in Los Angeles. They were standing under the soft sparkle of Disneyland lights. Emma had mouse ears on. They were laughing, breathless, flushed from a day of magic. It was the happiest they’d looked all week.

And I broke.

I smiled for them, I waved through the screen, I swallowed the rising bile. But the moment the call ended, I cracked. Because the best day of John’s life, in Disneyland with his daughter, was the worst night of mine. Our daughter. Sick. Hospitalized. Possibly dying. And only one of us was here, carrying the weight of not knowing.

They were flying home the next day—the flight we were all supposed to come home on.

My mom arrived the next morning with a fresh bagel and a shirt from home. My dad brought coffee and his usual dad-joke, trying to break the fog with something human. Mom held the thread of the normal so tightly that it didn’t snap.

They filled in the places where fear had hollowed me out.

They stood in the breach.

They reminded me I had not been erased by this.

But everything was changing.

And I could feel the weight of a word no one wanted to say.

Tumor.

It was still circling us.

Waiting to land.

And we were just holding, holding, holding—until it did.