2. Prague Castle & What it Means to Live Forever

Tuesday, August 5

It’s my birthday today.

And for the record: Mom vehemently objects to my claim yesterday that she only had two sips of beer and needed Rod to finish it. According to her she drank at least half. So. Let’s clarify: Mom’s truly a tank. She may have forced us to wait for an hour today while she finished one inch of beer for her own dignity but she’s absolutely not a lightweight.

So, back to today—celebrating my birthday with the Prague’s great Bohemian Kings.

We left our BnB in Praha 4 at 9 AM sharp, because this city rewards early risers—and also because I insisted we get to the castle early despite my late rising.

Our first stop was Caffe Vescovi at Újezd 36—a cozy little café on the slopes of Malá Strana with excellent cappuccino to go. So I could sip and walk… slowly talking myself up to the 1,000 flights of stairs we were about to climb.

We strolled up Újezd, turned left by St. Nicholas Bell Tower, veered right at the Holy Trinity Column, and started the ascent of Zámecké schody (Castle stairs)—a workout that definitely qualifies as cardio disguised as history. Today, I met my flights of stairs goal x100.

One my two boomers caught up to me, we made it to the First Courtyard of Prague Castle, where ceremonial guards (military, police) stood statuesque.

Side note: Czech people are on average more attractive. Maybe it’s the beer?

Prague Castle & St-Vitus Cathedral

I entered St. Vitus Cathedral and the first thing that struck me was the light. All colours. Everywhere.

There, on the stone wall to my left, a wash of colour moved like breath. The Alfons Mucha window—unmistakably his, all curved lines and halos—cast its long gaze across the nave. You’ve seen reproductions, of course. Coffee table books. Postcards. But seeing it in person was something else. The glass glowed like it had been lit from within. A modern insertion, 1931, and although the style was markedly different, it didn’t feel out of place.

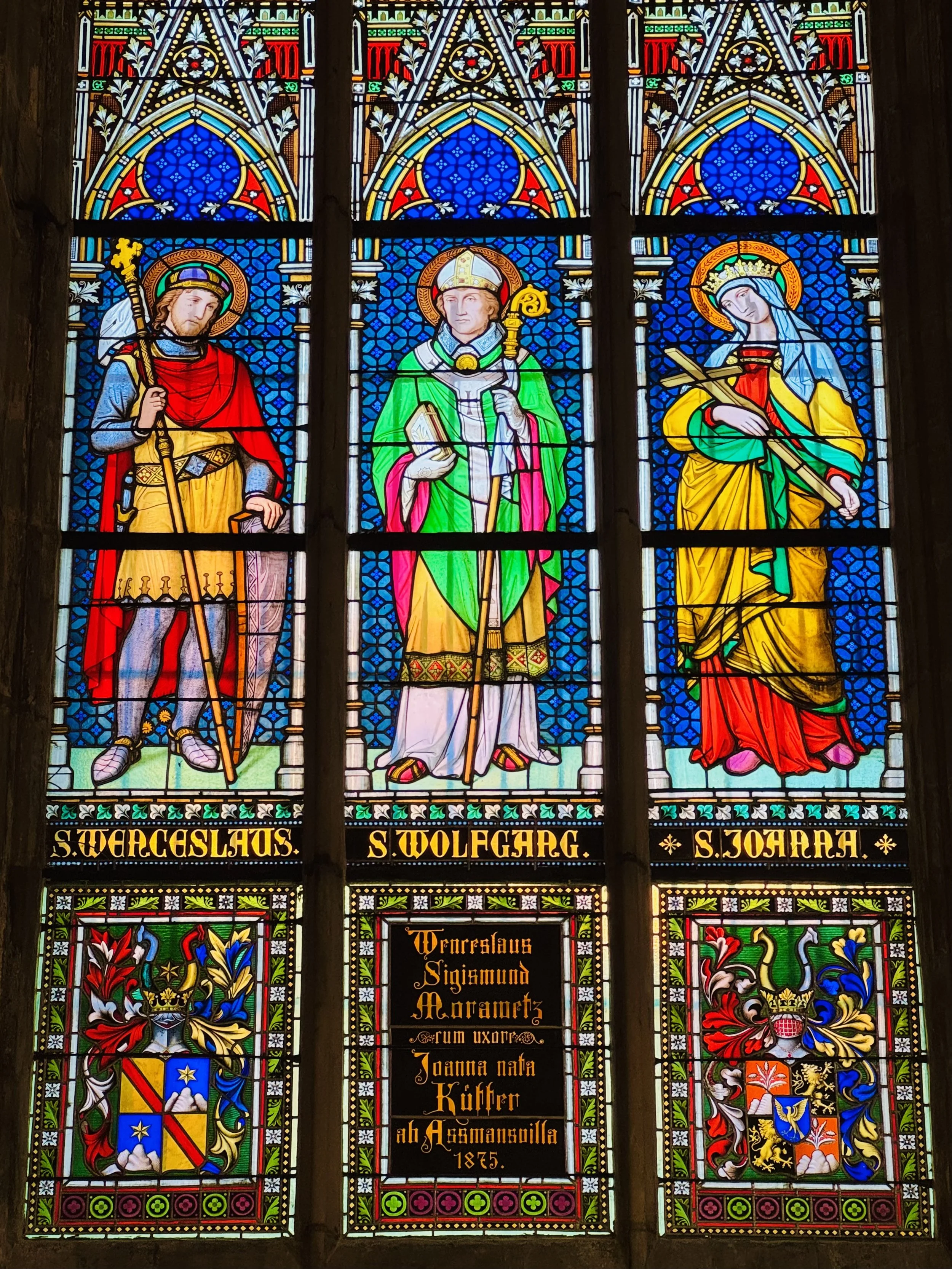

We made our way past chapels and altars that seemed to multiply like mirrors in a hallway. Each one more gilded or elaborate than the last. There was a chapel lined with semi-precious stones and guarded by frescoes the colour of dried blood. This was St. Wenceslas—patron saint, national martyr. They’d buried his bones in the walls, which struck me as both oddly intimate and wildly spooky.

Further on, the Royal Tomb. Charles IV lay there, among others—the emperor, the architect of Prague’s Golden Age. A slab of marble and a name. A man who changed history.

At one point, I passed a stone knight laid out in full armour, eternally at rest, shield in hand. Přemysl Otakar II.

It’s easy, at first, to walk past them the way one walks past anything old and labelled: a mix of interest yet detachment, as though they were exhibits, not people. But then something catches. A line on a plaque. The curvature of the eyes. And you start to consider what it really means—to be buried beneath centuries of footsteps, and yet still somehow known.

So I did a little research…

St. Wenceslas (c. 907–935)

St. Wenceslas, martyred by his own brother, sanctified by myth, his very bones held in the walls of a chapel that glitters like a jewellery box.

Wenceslas wasn’t a king, but a duke of Bohemia—though you’d be forgiven for thinking otherwise, given the reverence. He ruled in the early 10th century during a time when Christianity was still taking root in Central Europe. Wenceslas chose diplomacy over war. He built churches, promoted education, and attempted to steer his people away from pagan violence and toward something more stable—something more future-facing.

His brother Boleslaus, less interested in moral nuance, had him murdered. Legend says it happened on the steps of a church. That act of betrayal, and Wenceslas’ quiet sanctity, turned him into a martyr almost immediately. The Holy Roman Empire canonized him. And thus began the cult of St. Wenceslas: protector of Bohemia, moral conscience of the nation.

He is, in many ways, the soul of Czech identity. Not its architect, but its heartbeat. His statue stands in Wenceslas Square not because he built a kingdom, but because he gave the Czech lands something rarer: a guiding story.

Přemysl Otakar II (c. 1233–1278)

Přemysl Otakar II—known as The Iron and Golden King. A warrior by nature, he expanded Bohemian control across Austria, Styria, Carinthia, Carniola—basically half the Holy Roman Empire. He was brave, calculating, and dangerously ambitious.

This was a time when power was measured in land and blood, and Přemysl had plenty of both. But his reach exceeded his grasp. He lost the support of the Pope, alienated powerful nobles, and eventually died in battle at the Battle of Marchfeld—cut down in full armor, his body left in the dust until his enemies decided to give him a burial befitting a king.

He represents the brawn of Bohemia—its capacity for dominance, its military pride, and also its tragic limits. His death marked the end of expansion, and the beginning of something more internal.

Charles IV (1316–1378)

And then, Charles.

Born in Prague, fluent in five languages, educated in Paris, crowned Holy Roman Emperor. Charles IV didn’t just lead Bohemia—he transformed it. Under his reign, Prague became the capital of the empire. He built Charles University in 1348—the first in Central Europe—and oversaw the construction of Charles Bridge, St. Vitus Cathedral, New Town, and the Karlštejn Castle.

But it wasn’t just architecture. It was identity. Charles believed in the sacredness of Bohemia as a nation, not just a territory. He wrote the Golden Bull of Sicily, securing Bohemia’s status as a hereditary kingdom. He patronized Czech literature and codified law. He turned the Czech lands from a peripheral duchy into the beating cultural heart of Central Europe.

Where Wenceslas gave it soul, and Přemysl gave it strength, Charles IV gave it structure—lasting, literate, spiritual.

There’s something humbling about standing in the presence of these great Bohemian Kings. Not because they were perfect. But because they live forever here. Their bodies are long gone, dust in sealed tombs, but their names still hang in the air, repeated by visitors, printed on plaques and prayer cards and school essays.

To walk past them is to walk through time. To feel, if only for a moment, what it meant to be Bohemian—not in the modern, café-sipping sense, but in the older, deeper one. Before it was Czechia, it was Bohemia. Before that, a people. And before that, the human longing to belong… to a something, as a someone… somewhere permanent.

Before we could burst into flames, we left the cathedral and proceeded through the grounds into the Old Royal Palace, the oldest part of Prague Castle, where politics once lived before the baroque façades took over. The Vladislav Hall remains the architectural showpiece—a vaulted stone ballroom of gothic ambition, grand enough to host banquets, markets, coronations, and, most interestingly, mounted knights performing indoor jousts. As one does. The hall offers a discount for any off-season jousting.

Outside, I tried to picture the famous defenestrations—an infamous Slavic diplomatic solution involving the swift ejection of one’s enemies through a window. (In this case, in 1618, two imperial governors and a secretary were thrown from the windows of the Bohemian Chancellery. They survived, allegedly by landing in a pile of manure. The Thirty Years’ War was less forgiving.)

From here we moved toward the Rosenberg Palace, once the seat of a powerful noble family, later transformed into a residence for unmarried noblewomen—a sort of aristocratic nunnery for those considered unfit or unwilling to marry. In a different century, it might’ve been a reality show. Whatever it was, the idea of women living in their own secret girls palace sounds like a party and my ideal life.

Then we entered the Golden Lane—a row of miniature houses clinging to the inside of the castle walls, like something out of a grim fairy tale. The lane once housed castle guards, seamstresses, goldsmiths, and—most famously—alchemists. The staff were clearly afforded the smallest possible space to live while serving their betters. Rooms now are arranged into scenes, such as in the herbalist’s shop where jars are labelled for all manner of things you probably shouldn’t ingest. Although I wouldn’t have blamed them for slipping something awful into a Lordling’s ale.

Once we had our fill of pious faces sculpted in gold and the plight of the have-nots, I heard my mom saying something about a nearby monastery that brewed its own beers. I was not informed that monks tend to do this. Now this all sounds like men living in a secret man palace making beer together and partying nonstop.

Maybe the key to happiness is just living with your best friends and drinking?

To discover the truth, I led our trio out of the castle into the Hradčanské náměstí—the square at the top of the castle hill. At this point, the sun had risen to nearly noon, the crowds thickening, the city below us humming. It was absolutely lunchtime. And after what felt like 1,000 stairs, the team agreed it was time for refreshments.

We passed Černín Palace, an imposing, rather severe 17th-century baroque slab of a building, now home to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Once built to impress the Habsburg court, it now functions mostly as a backdrop for awkward diplomatic photo-ops and strategic parking.

Finally, we arrived at the gates of Strahov Monastery. This alone felt like a pilgrimage. Mom told me that she and Papa (Zed) had stayed here at the monastery hotel years ago. So in many ways we were retracing their steps… right towards the brewery.

As we entered the fine establishment, I found myself thinking less about religion and more about the unbroken line of intention it takes to keep a place like this functioning for nearly nine centuries… hops intact.

The monastery intrigued me so as Rod went to fetch our ales, I looked up the details. Founded in 1143, the Strahovský klášter belongs to the Premonstratensian Order—a Catholic order of canons regular, neither monks nor priests exactly, but something deliberately in between.

I might just call them Brewmasters.

And the Strahov Monastic Brewery has been brewing beer in some form or another since the 13th century - aka actual medieval times. Though the modern incarnation is considerably more efficient and less likely to invoke divine intervention.

Whatever your thoughts on God, continued beer excellence deserves respect. And so we decided to honour the beer gods just a hair shy of noon.

The house brew, Sv. Norbert amber ale, was excellent—honey-toned, malty, and entirely perfect for a trio who’d just climbed half of medieval Prague before noon.

We decided to pair our ales with a side of lunch. I ordered the tomato burrata, a futile attempt at veggies in a land deeply committed to meat. Mom had the chicken with potatoes. Rod chose the goulash and dumplings. Between them, it was a tour of the Bohemian food pyramid: meat, starch, more starch, and beer.

At one point, half a beer in, Mom reminded me of my libellous claims against her in yesterday’s blog. She reminded me of my commitment to right the wrong in my libellous blog post yesterday and she proceeded to assert dominance by finishing my beer. On my birthday. A bold move, delivered without comment or apology. I chose not to contest it—as I didn’t want our seatmates to be concerned for my mom’s safety.

We sat at a long wooden picnic table under a canopy, sharing the space with two German grandmothers who spoke no English. I attempted a few sentences via a translation app. It did not go well. One of them smiled kindly. The other looked unconvinced. But I think they liked us.

After lunch, I visited the brewery shop, where I bought two secret gifts—the coolest I’ve ever seen. More 1980s punk band than sacred monastic relic.

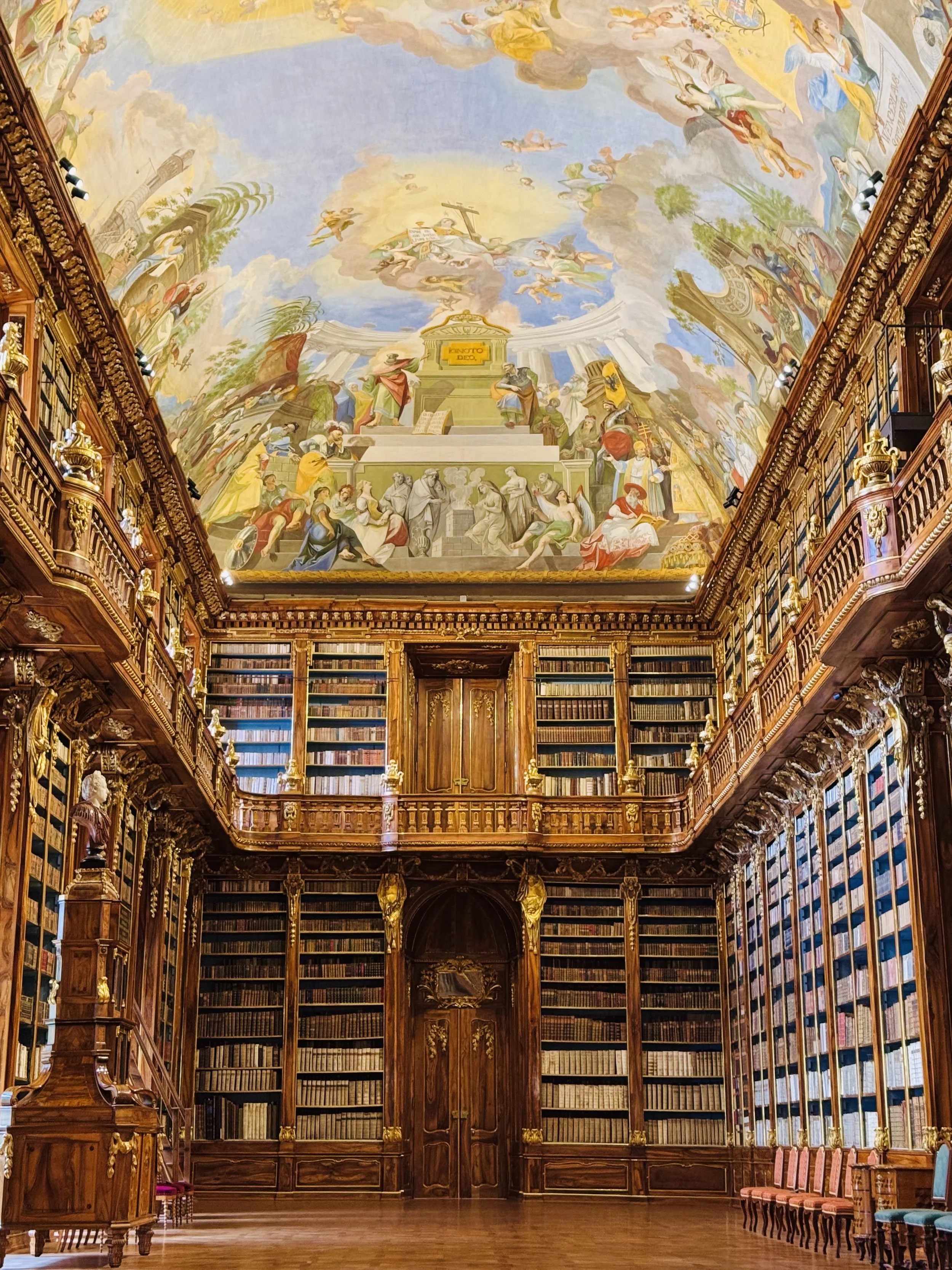

From there, we ventured into the Strahov Library, which appears to have been built as a place to read books but is now primarily used to make people gasp. Is it really necessary to be this ornate? Is this what the church does with donations? The Philosophical Hall, with its ceiling frescoes and walnut cabinets, is almost impossibly ornate—so much so that a scene from James Bond (Casino Royale) was filmed here. Bond didn’t read anything, of course. But he did stand around looking meaningful. We followed suit.

Out into the light again, we descended to the Strahovská vyhlídka—a lookout point that gives you what might be the best view of Prague. The whole city stretched out before us: domes, bridges, terracotta roofs, and the soft gleam of mid afternoon light bouncing off statues of brass babies climbing a Soviet era tower used to broadcast propaganda - completely normal. It felt less like a panorama and more like a painting of rich history to be enjoyed with a draft. Preferably made by monks.

We took the Promenáda Raoula Wallenberga, a path named for the Swedish diplomat who saved thousands of Hungarian Jews during the Second World War. It was a quiet stretch, well-shaded. Fitting.

We hiked up Petřín Park, where we stopped at the base of the Petřín Lookout Tower—Prague’s answer to the Eiffel Tower, only significantly smaller, and on a hill, and slightly resentful of the comparison. We didn’t ascend it due to survival instincts. Instead, we sat on the patio and ordered more beers as it had been at least one hour since our last refreshment. Predictably, Mom claimed to be “feeling dizzy” and couldn’t finish her beer and passed it to me, this time without comment. Possibly a peace offering.

I tried to make her feel better by asserting that I am, in fact, the family tank.

We continued our hike down past the Hunger Wall, originally built during the reign of Charles IV as a way to provide employment during famine—a rare historical example of public works meeting public needs without too much fanfare. We passed by the Magical Cavern, a former quarry that now houses mildly psychedelic art and a certain odour of shroom mystery. I saw approximately three white people with dreadlocks in the vicinity.

At some point during all this, Rod, mom, and I agreed we should get matching tattoos to commemorate the trip. A joke, probably. Or perhaps not. We were several pints in by this point. Rod, our team-appointed Chief Decision Officer, declared that if you, dear reader, have read this far, you may cast a vote on what tattoo we shall get. Democracy in its purest form.

Eventually, we descended all the way down to Náměstí Kinských, which seemed appropriate as Zed is a descendant of the Kinský noble family, and the square is named after them. We’d started the day in the domain of Kings and ended it in the square named for a noble family that understood how to quietly hold power for several centuries.

We walked to Tesco to gather snacks and provisions—small bribes for tomorrow’s morale—and then back to Plaská 4, our BnB condo to consider our day over another pint or two before dinner.

We climbed thousands of stairs and took 15,000 steps today.

Had several beers at several different patios.

Ate bread in six different forms.

Saw some old stuff.

And, for a few moments, remembered what it feels like to be both fully beered and grateful for this life.

And to end the day, I’d like to share a reflection that has been on loop in my mind.

A year ago today, at four in the afternoon, I sat across from Zed in the quiet of my parents’ home. He had spent the day in the emergency room—another long, fruitless battle with the side effects of cancer treatment. His body was failing under the weight of the cure.

He told me, gently but deliberately, that he had made a decision. He was stopping the chemo. Stopping the radiation. Stopping all of it.

He was afraid to tell me. He said so. I had fought so hard for him to get treatment as fast as possible. But he wanted to be honest. He didn’t want to live sick. The treatment was making him sick, not better. He was in pain. What time remained, he wanted to spend living, not enduring.

We talked. Not everything. But enough. I asked him what he wanted to do with whatever time we had left. We still thought there would be weeks. Maybe even months. I told him I wanted to take him back—one last time—to Czechia. Back home. I was already searching for tickets. I had a plan forming. In my mind, he had to see it again. And in my heart, I knew I should have brought him years ago.

Rod is here now, because Zed was his best friend for over forty years.

My mother is here because Zed was her husband.

And I am here because I am his daughter. And because this—whatever this is—is part of how we try to process, try to make sense of what it means to say goodbye.

We will see his Czech family. Hold a service. Scatter his ashes. Walk the streets his ancestors once walked. Honour where he came from. Zed Tůma—descended from the great Bohemian nobility, the Kinský line—was himself a great man. He has no tomb in St. Vitus Cathedral. No gilded altar. No sarcophagus passed by tourists and schoolchildren. But greatness isn’t always carved in stone.

My children have asked where the dead go, and we answer gently: “They live on in our hearts.” Maybe that’s why we’re here. Maybe that’s what this trip is.

One year ago today, Zed told me he was done fighting.

Four days later, he died.

We thought we had more time.

We never know what time we have left.

Now we carry him. The memories. The stories. The ash. The love.

We carry what it means to live forever.

In our hearts.

And we keep walking.

And something tells me that he’s walking right beside us.