3. České Budějovice & Masné krámy

Dear Reader, I apologize for missing a blog day. Yesterday, we suddenly became inebriated.

Not “lost-my-passport-in-a-fountain” drunk, but certainly past the point where anyone should be operating a keyboard or making grammatical decisions.

We now return to your scheduled programming, slightly dehydrated but spiritually enriched…

Where were we? Ah, yes: back to Wednesday, August 6

I woke up late, as one should on a vacation, to the unmistakable sounds of boomers doing things in the kitchen. The soundtrack included heavy-footed movement and overuse of cupboard doors. I also heard the unmistakable sound of my mom inquiring when I’ll get up with Rod mentioning something about soft millennials.

I flung out of bed and we packed to check out of Plaská 4 and head toward our next stop: České Budějovice, via a rental car pickup by 1030am.

While waiting for the Uber, I popped into a local café to grab a cappuccino. I got exactly to the payment screen before the Uber arrived early, at which point I had to make a tragic choice: abandon the cappuccino or delay my increasingly tense travel companions. I made the mature, self-sacrificing decision. The cappuccino was re-homed to a better family.

Our Uber driver spoke no English but communicated efficiently via existential despair. Russian, I think. Possibly Chechen. He seemed dangerous. It was hard to assess for sure, as he seemed to be on the verge of falling asleep while driving through Malá Strana’s tightest curves. I kept my eyes on the road and my mouth shut. We arrived alive. That’s all that matters.

The rental pickup—at AutoUnion Car Rental, Prague Airport—was mercifully uneventful. Documents, keys, the usual waiver about not crashing into any castles.

Notably, the clerk told me “don’t go faster than 150/km per hour—our roads are only 130.”

Which made my brain explode.

Anyways. Next stop: Písek.

Let’s see what South Bohemia has in store.

We stopped in Písek just after noon. A small South Bohemian town with a quietly proud air and suspiciously well-preserved medieval defences, it holds a particular significance in our family story. Over lunch, Mom told us that Písek was where Zed had been stationed during his military service in 1975, back when Czechoslovakia was still under communist rule.

He was twenty, university-educated, and—critically—actually smart. This combination made him stand out just enough to be plucked from the ranks and made the colonel’s aide-de-camp. Most recruits stayed on base. Zed, however, was given a sidearm and a surprising amount of trust. He was sent regularly into Písek on “official business,” which included two critical wartime functions: picking up payroll cash from the local bank, and smuggling Scotch back to the base for the colonel.

We traded more stories over the meal at a local Czech restaurant. Dear reader, I had the chicken schnitzel and it was absurdly good—crispy, tender, seasoned like someone in the kitchen didn’t speak a word of English.

After lunch, we walked down along the Otava River, past a row of cheerful, pastel-coloured homes that looked like someone had sorted them by Pantone. The whole riverwalk is manicured, calm, and a little surreal—until you reach the crown jewel of Písek: the Kamenný most, or Písek Stone Bridge. Built in the 13th century and older than Charles Bridge in Prague, it’s the oldest surviving bridge in the country. Still standing. Still stunning. Medieval AF.

We crossed it on foot, passing sand sculptures from the annual Písek Sand Festival, including an ornate carving of imperial coats of arms, lions, and crowns—all of it slowly eroding in the sun, which felt a little on the nose.

Just past the bridge is the Prague Gate—a former city gate from the 13th century that once guarded the town’s perimeter. In true medieval efficiency, it was a trap-style gate that could be raised and dropped vertically, blocking out enemies and, presumably, taxes. It was demolished in 1905 but lovingly documented in surviving sketches and now reconstructed in signage for the curious and nerdy (hi).

Somewhere between the schnitzel and the sandstone lions, I felt Zed there—twenty, cocky, on a mission for contraband whisky, and maybe a little pleased we remembered all of this.

Finally, we strolled past the Putim Gate, another of the city’s defensive relics. It was locked, which I respect. There’s something delightful about a medieval town that still won’t let you in.

So that was Písek. A place where Zed once fetched scotch under a dictatorship. Where payroll meant carrying bags of money under military protection. Where he found a pocket of autonomy during years when most people were being watched.

I don’t know if he loved Písek. But he remembered it. And now, so do we.

We had enough of Pisek and pressed further south, cutting through the České Budějovice region with an enthusiasm only partially undermined by our mounting disagreements about the correct route. Rod and Mom are Google Maps people. I, a loyal Apple Maps apologist, insisted on “my way” with the calm(ish) authority of a dictator in leggings. We soon found ourselves on country roads barely wide enough for two cars… that looked like Mario Kart tracks but without the safety railings. If I ever become religious, it will be because of Czech backroads and how narrowly we escaped becoming sausages for the wild boar population.

Eventually, we descended into České Budějovice, the largest city in South Bohemia—known to the rest of the world primarily as the birthplace of Budweiser (the original, not the American abomination). The Austro-Hungarian influence is palpable here, with wide Baroque squares, a chessboard layout of pastel buildings, and a quiet kind of grandeur that doesn’t try to seduce you—it just is.

We parked at the Airbnb, cracked open a couple of local beers on the patio, and discussed Saaz hops like we were contestants on Master Cicerone: Bohemian Edition. Zed would’ve approved. Saaz hops, I learned from Rod, are the soul of Czech brewing—low bitterness, high aroma, and the floral backbone of any proper pilsner. If you’ve ever had a beer that tastes like the first five seconds of falling in love, it probably involved Saaz.

Then: a walk through the park, where there was a contemporary art festival in full swing. Giant tile men lounged in the grass, not quite statues, not quite furniture. Public installations were scattered throughout—some whimsical, some bleak, some confusing even with the explanatory placards. One sculpture looked like a sad, Soviet-era transformer. I sat on it anyway.

From there, we made our way into the heart of the old town. The Náměstí Přemysla Otakara II—one of the largest town squares in Europe—unfolds like a movie set. Stately buildings in yellows and creams surround Samson’s Fountain (named after the beer), which was mid-pee when we arrived (artistically, of course). Seriously, it’s a bizarre statue of a man riding (possibly while murdering) a pig and this is the centre of the town square.

Nonetheless, the square still holds echoes of the city’s liberation by American troops in 1945—something not often highlighted in post-communist tour books, but proudly displayed here with a modest but poignant exhibition. Let’s not forget how many times the Bohemian people were conquered and liberated.

Then, the Black Tower. Černá věž. A 16th-century bell tower originally used for surveillance, status flexing, and reminding the citizens who was boss. Mom spotted the narrow doorway and immediately charged upward like a harpy with a mission. I followed for about 40 steps before the existential dread of endless medieval spiral staircases took hold, and I staged a quiet retreat. Unlike everything in nanny state North America, here they just let you choose your own adventure with very little instruction.

Rod, in his wisdom, hoofed his way up the staircase like an energetic mountain goat. He texted us halfway saying it wasn’t that bad and I told him my mom would join him… as I ran in the other direction.

While I waited for Brave Rod, I shopped for more Secret Gifts for the kids. Stay tuned on that!!!

Eventually, beer called us all. It had been HOURS since our last one.

Reunited, we three walked by the bakery Mom once visited with Zed. She lit up when she recognized it. Something about the familiarity of homemade bread and coffee when nothing else in life makes sense.

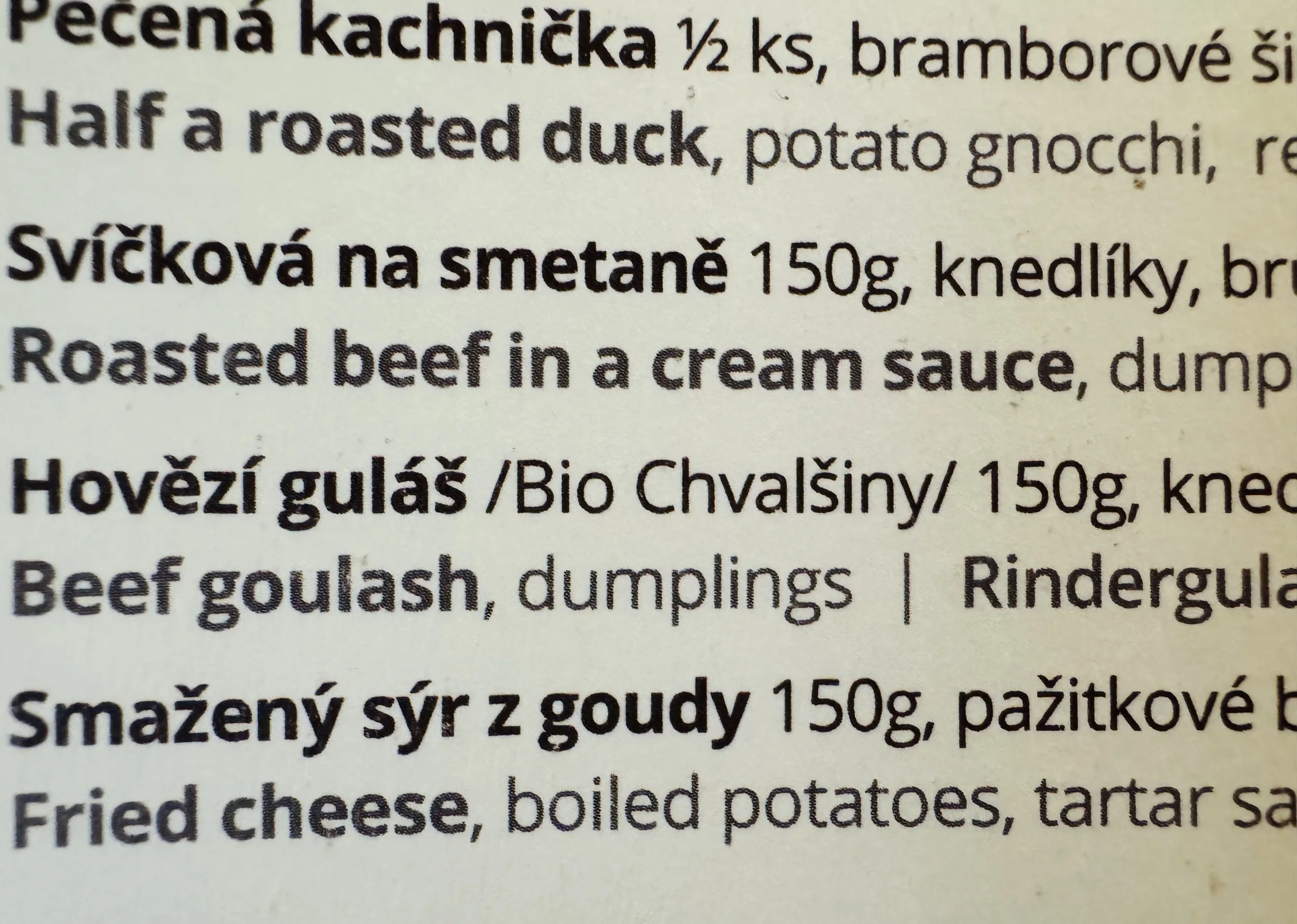

Dinner was at Masné krámy (literally “meat shops”), a famous beer hall that once sold butchered goods and now deals exclusively in the delicious destruction of one’s dignity. The food was phenomenal. The beer was better.

And that’s where the story dissolves into a contest of how many Budvar variations we can ingest.

That evening, we made many important decisions over beer (of course) at Masné krámy, which I’m now convinced is my new spiritual home. I want to live in each nave. Or at least buy the glassware.

If Zed were here, he would try to charm the waitress into giving him the mugs for free.

My mother, who started the evening in reasonable form, suddenly remembered that she and Zed once got gifted actual Pilsner Urquell glassware from Křivoklát Castle, a place so old it was giving out merch in the 11th century.

At one point I declared that the men here are much hotter than expected. Mom leaned over and whispers, in that hushed, conspiratorial tone she reserves for her spiciest takes:

“The men here all have big heads.” And she then adds, “That’s why they are all bald. It pushes the hair out.”

Direct quote. Apparently the Czech Republic is a land of gentle giants with enormous skulls and even bigger brains. Her words, not mine.

The drinks tally goes as follows:

Mom: 3 pints. Respectable (?)

Me: 5 pints. Spirited but stable.

Rod: 8 pints. We’ll circle back to this.

We eat more. It’s hearty and hot and I don’t remember exactly what I ordered but I remember it was perfect.

We wander. Through České Budějovice like locals who just happen to stop every few blocks for another pint.

We debate how to measure head circumference without people knowing it, to prove or disprove my mom’s theory.

We find a bar on the river with what can only be described as a Beer Ledge over the river. Literal perfection. I have photo evidence.

Then, because this night has no rules, on our way back to the BnB, we stumble across a DNB festival in the park.

Yes, you read that right: Drum and Bass, in a Czech courtyard, after dark and with black lights.

Trying to explain dubstep to my mom while drunk-walking home through České Budějovice was, honestly, the kind of absurd joy that should be bottled and sold.

I started by saying it’s kind of like techno, but angrier. I tried again: “It’s like… if a robot had a panic attack in a car wash.”

The bass from the DNB stage is still rattling our ribs as we meander along the riverside.

Later, I’m in bed, still a bit buzzed, and I start scrolling through pictures of my kids. I miss them. That low ache of absence—the good kind, the love kind—just sort of sits in my chest.

It made me think about what it means to bring someone with you after they’re gone.

And maybe that was a good thought to end the night…

Final Thoughts