4. Zámek Český Krumlov

Thursday, August 7

We left České Budějovice around 10 a.m., fortified by espresso and a lingering hangover, bound for the storybook sepia of Český Krumlov. The drive south is only an hour, but feels longer in the way dreams do—forests unspooling, terracotta villages appearing out of mist, and somewhere in the Czechia-Austria foothills, an entire medieval town pretending the last five centuries didn’t happen.

Český Krumlov is one of those places that—if you described it too earnestly—would sound made up. A baroque reincarnation. A Renaissance film set. The whole thing is bent like a question mark around the Vltava River, its narrow cobbled lanes sloping toward a town square so postcard-perfect it’s almost unbelievable.

We found parking, then followed a shaded trail that climbs through the forest like some forgotten servant’s path. The kind of entrance meant for staff, not sovereigns. But it delivers us to the high gates of the castle like magic anyway, emerging beside ivy-covered walls.

The castle itself—Zámek Český Krumlov—is the second largest in the Czech Republic, after Prague Castle, and makes no small effort to remind you of its grandeur.

Up on the castle walls, we enjoyed the view of the entire town below. Someone nearby hired a guide, who happened to be English. I leaned in and listened. Apparently Český Krumlov exists, more or less, because it didn’t burn down. That’s the short version.

While fire, war, and modernization chewed through much of Central Europe’s medieval architecture, this town—tucked in a meander of the Vltava River in South Bohemia—managed to survive largely intact. It wasn’t especially strategic, wasn’t a capital, wasn’t a hub of anything during the industrial boom. Which is precisely what saved it. In a rare twist of fate, obscurity became preservation.

I walked a few feet away from the guide and his paying visitors, just close enough to learn that the town dates back to the 13th century. Its name comes from the German Krumme Aue—“crooked meadow”—per the river’s serpentine shape. It grew under the rule of the Lords of Krumlov and later the Rosenbergs, one of Bohemia’s most powerful noble families.

Thanks to their influence, the town became a minor cultural and trade centre, especially in the 14th and 15th centuries. You can still see the original street layout, narrow and organic, curving with the land. Most of the buildings in the historic centre are late Gothic, Renaissance, or Baroque—stacked on top of each other like sedimentary layers. Some of them haven’t changed in 500 years. The guide concluded that it’s one of the best-preserved medieval towns in Europe, not because of constant restoration, but because no one got around to ruining it.

I explained this to mom and Rod as we walked down through the castle, but probably not quite getting it right, as I’m known to do.

Then, on our way out of the castle, we walked over the moat. The castle moat is populated not by water but by actual brown bears, a tradition held over from the days when the ruling Rosenberg family claimed descent from the Italian Orsini (whose name and crest featured a bear, because symbolism has always been indulgent). These modern moat-bears are reportedly well-fed and somewhat bored, which is to say, they are European…

I was curious so I researched a little more about the castle. I learned that the castle—Zámek Český Krumlov—was first built in 1240 by the Lords of Krumlov, and like most castles, it’s been expanded, rebuilt, and added onto in stages, depending on who was paying the bills. When the Rosenbergs took over in the 14th century, they turned it into a proper seat of power: added fortifications, built the upper castle, commissioned frescoes. The bear moat came later, part status symbol, part live-in family crest.

In 1602, the Rosenbergs sold the estate to Emperor Rudolf II (they were broke), who then handed it to the Eggenbergs, an Austrian noble house with a taste for Baroque flair. They built the castle theatre, one of the oldest surviving Baroque theatres in the world, still complete with original stage machinery and costumes. Then in 1719, the castle passed to the Schwarzenbergs, another powerful family who kept the estate until 1947.

After WWII, the communists nationalized the property, like everything else of value. The castle and the town stagnated under state ownership, which paradoxically protected it from overdevelopment. Since the fall of the regime, Český Krumlov has been slowly polished into a UNESCO World Heritage Site, a cultural darling of tour groups and river cruise brochures.

Anyway, after the castle we went into the Old Town, full of shops, arts, and intrigue. We stopped into an Old Bohemian Gingerbread Shop that also made its own Slicovice and more!

Somewhere between the bear moat and the Slivovice, hunger struck. We found a spot by the river that specialized in food priced for people who say things like “Honey, will you be taking the Benz or the Ferrari?.”

Determined to hit his protein requirements. Rod ordered a roasted pork knee the size of a toddler. Mom went with a chicken steak. I had schnitzel, obviously. The beer was cold, the sun was high, and spirits were similarly elevated—until Mom, predictably, couldn’t finish hers.

Incriminating footage exists of her subtly pouring the remainder into Rod’s glass. The crime was swift, but not clean. She was caught mid-pour.

This was about the time that I was discussing the next-thing plan with Rod. The man, ever the philosopher, dropped some wisdom:

“Never leave your current beer place without knowing your next beer place.”

Words to live by. And we chose to.

Next stop: Pivovar Český Krumlov, a brewery with branding that looks like it was designed by a medieval herald and a hipster graphic designer in equal measure. Inside, the beer lineup reads like an armory: Krumlov 11°, Krumlov 12°, APA Citra 11°, dark smoked lager, and one lone citrusy outlier with lime. Everything’s hand-pulled, cash-only, and charmingly Czech. Above the taps, a puppety little bearded man floats in a hot air balloon rigged from wheat and whimsy. No explanation given. None needed.

I, of course, led us to the wrong location first (thank you, Apple Maps), but eventually course-corrected. The walk along the river made up for the detour, and besides—travel is just structured wandering with snacks.

And, as an aside, Dear Reader, are you worried I’m roasting my mom too much? Don’t be. I’m getting torched right back. Rod and Mom have teamed up to remind me, repeatedly, that I am a soft millennial who needs naps, snacks, Apple Pay, and emotional prep before crossing a bridge or reading a menu. Also, their faith in my navigation is declining with everyday.

Losing my way onto the Eggenberg pub was the final straw: but nonetheless we got there and enjoyed more history, more branding, more opportunities to spend cash I didn’t have. But the beer? Absolutely worth the hassle.

So here’s what I’ll say about Český Krumlov:

It’s not just that the buildings are old. It’s that they feel old, and unbothered by you. This town doesn’t need your approval. It already outlasted your empire.

And it serves a damn fine lager.

Even if my mom didn’t finish hers.

Dear Reader: I know what you’re thinking. “If you never leave your current beer place without a plan for your next beer place… then what was the plan?”

Excellent question. And you’ll be relieved to know there was a plan—two more beer places, to be exact—and it was already edging dangerously close to 3 p.m. That gave us about two hours to get our asses back to České Budějovice before both Pivovar Samson and Budvar closed.

Now, my mother—bless her certainty—insisted that Samson wasn’t going to be a thing.

“There’s no bar,” she said.

“It’s not open to the public,” she said.

“It’s a warehouse,” she said.

And she was right. But also wrong… (stay with me…)

See, Samson was the beer Zed and I used to talk about. The dark one. The one that vanished from Canadian shelves years ago like a beloved character written off a show mid-season. It was never fancy, never mainstream. But it was ours. The plan had always been: someday, we’ll go there together.

Well, “someday” has a habit of turning into now, and sometimes you follow a ghost into an industrial park to honour that.

So yes, we went.

I had to go.

Yes, it was a warehouse. Yes, there was no bar. Yes, the security guard was deeply confused about why a pink-haired Canadian and her equally foreign-looking entourage were trying to break into the side entrance of an operational brewery. But she was kind enough to point us toward the customer-facing “cash and carry,” where I bought the unfiltered lager and—more importantly—the dark one. The one I’d come for. The one we’d talked about.

And then, like a trio of mildly drunk pilgrims on a ticking clock, we gunned it to Budvar. Got there in time. Snapped the pics. Checked the mental box.

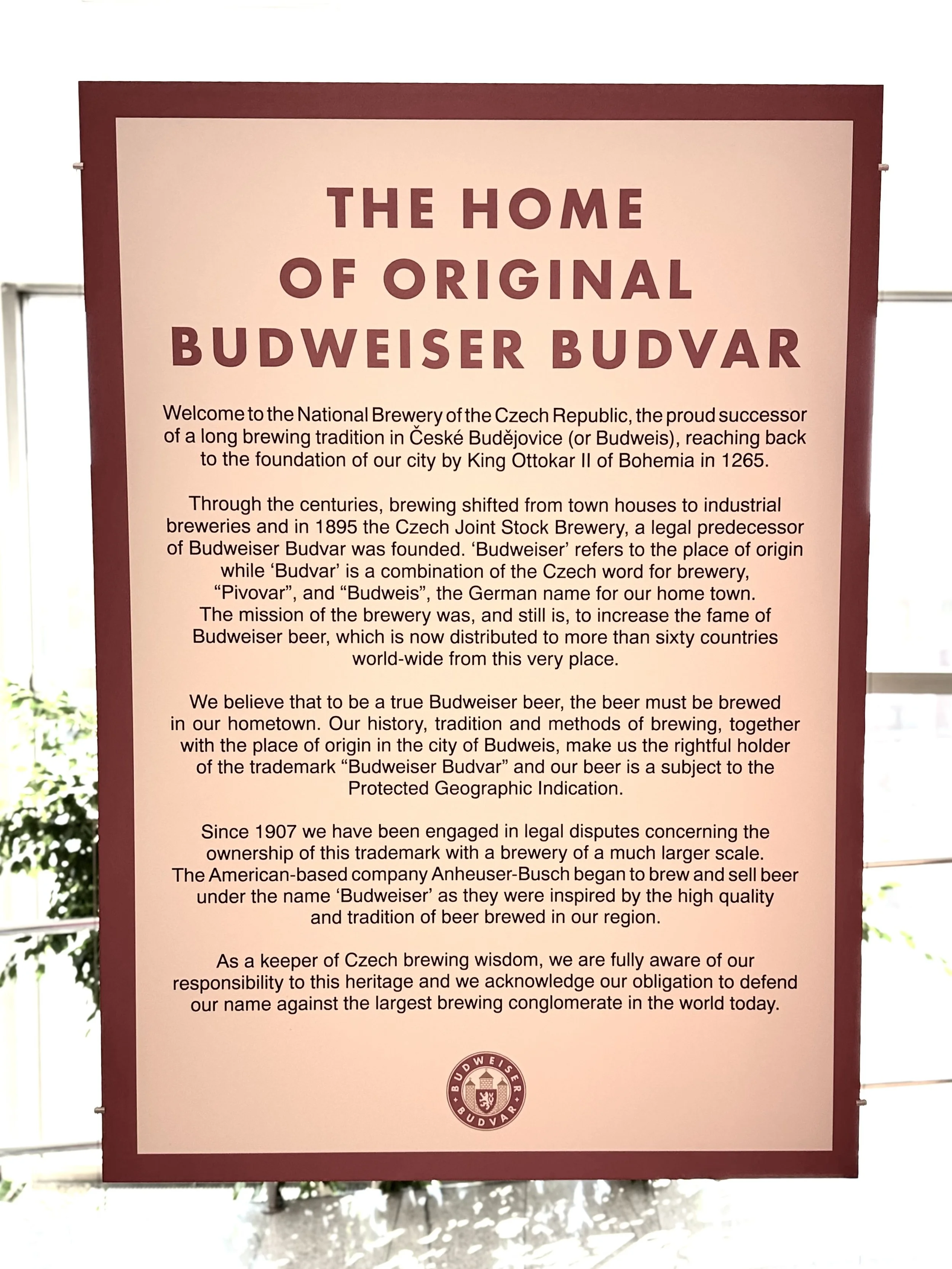

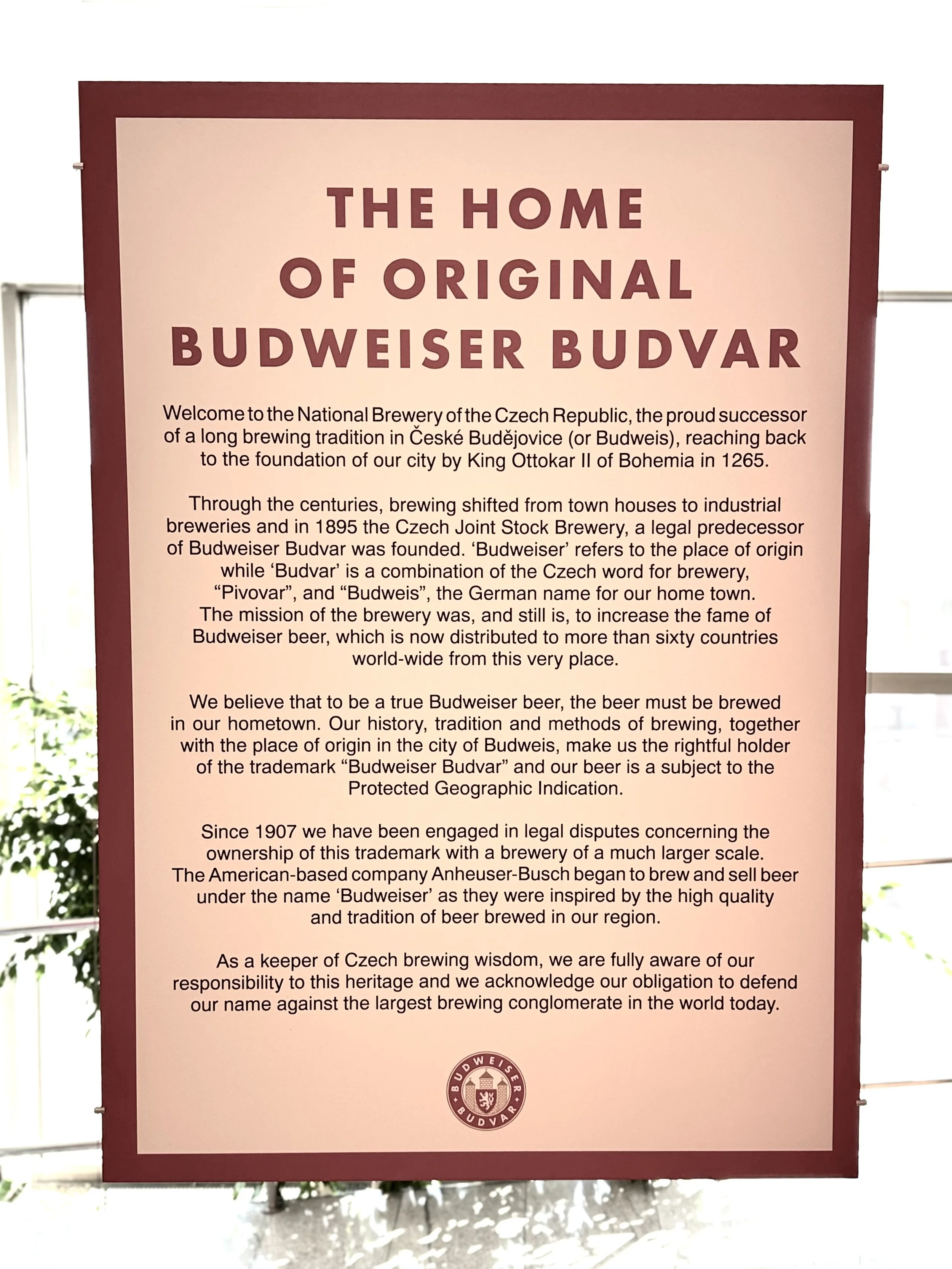

Here’s the thing about Budvar—or, as we tragically mislabel it back home in Canada, Czechvar.

Why the name change?

Because America, that’s why.

See, in the Czech Republic, Budvar is the national beer. Brewed in České Budějovice (which the Germans used to call Budweis), it’s been made with the same artesian water, Saaz hops, Moravian malt, and centuries-old attitude since 1895. This beer is protected. Revered. Probably knighted, if beer could be knighted.

But then in waltzes Anheuser-Busch, who took the “Budweiser” name in 1876—after Czech brewers had been making Budweiser-style beer for centuries. Cue the decades-long legal drama: international lawsuits, bitter disputes, and more trademark battles than a Marvel franchise.

The result?

In North America, Budvar isn’t allowed to use the name Budweiser, even though it was kind of the Budweiser before Budweiser was Budweiser.

So they rebranded to Czechvar for us.

(Which, let’s be honest, sounds less like a legendary beer and more like a knock-off Nordic tech startup.)

Now—Zed loved telling me this story. He told it like folklore. Like beer gospel.

I couldn’t believe it at first … how could it be? But he was right.

He had a whole thing about how we’d been sold a lie with our watery domestic Bud and how Czechvar—actual Budvar—was the real stuff.

The OG.

The truth.

Quality meets deliciousness.

And once you taste it here, fresh from the source, you get it.

It’s got flavour. Backbone. Dignity. Like your dad in beer form. Medicinal. Herbal. Just damn good.

It doesn’t need Super Bowl commercials or NASCAR sponsorships. It just needs a glass. And maybe a little national pride.

So yes, we call it Czechvar.

But around here?

It’s Budvar, baby.

The one true Bud.

Now we’re back at the BnB, beers chilling, and the conversation shifts to where we’ll scatter Zed’s ashes. That part is still a question mark.

But this part isn’t:

When we do it, I’ll be holding a Samson dark.

The beer that made it home. Even if he didn’t.